(CNN) -- When 2-year-old Malyia Jeffers developed a fever one Sunday afternoon in November, her parents gave her a children's Motrin and kept a cautious eye on her throughout the night.

By the following morning, Malyia's fever had jumped to 101 degrees, and other concerning symptoms also started to appear.

"I noticed bruising on her right cheek. She was really weak and could hardly walk," says her father, Ryan. He and his wife, Leah, drove Malyia to the emergency room at Methodist Hospital, five miles from their Sacramento, California, home.

According to Jeffers, a triage nurse briefly examined his daughter and said Malyia most likely had a virus and a rash, and told the family to wait.

They waited -- and Malyia got worse.

After two hours in the ER waiting room, Malyia couldn't walk or even stand up. "I tried to stand her on her feet, but her knees buckled," her father says.

Malyia's fever went from 101 to 103 degrees. Then, Jeffers says, the bruising on his daughter's cheek, once the size of a marble, covered most of her face and ears.

Jeffers says he returned to the emergency room nurse, who repeated that Malyia had just a virus and a rash.

"I told him, 'This isn't normal. Look at her ears,' " Jeffers recalls saying to the nurse. "'A rash isn't black and blue!' The nurse kept telling me, 'You'll be next, you'll be next.' But we saw other people going back before us."

Jeffers says he carried Malyia around with him while constantly complaining to the staff while his daughter continued to grow weaker in his arms. The couple discussed switching to another hospital but thought they would be seen soon and they didn't want to lose time.

They continued to wait.

The Jeffers finally see the doctor

After what her father says was nearly five hours of waiting in the emergency department, Malyia's body went limp. For Jeffers, the wait was over. This time he bypassed the desk where the emergency room nurses sat and pushed through the doors behind them.

"I asked to see someone different," Jeffers says. "I showed another nurse the bruising and said, 'Does this seem like a rash to you?' The nurse said, 'No' and put us in a room right away."

Jeffers says blood tests showed Malyia's liver was failing. She was sent by ambulance to a nearby hospital with a pediatric intensive care unit, which diagnosed a strep A infection. Also called the "flesh eating bacteria," strep A had sent Malyia into toxic shock.

Malyia was transferred once again, this time to Lucile Packard Children's Hospital at Stanford University. By this time, the prognosis was more grim.

"It was hour to hour, sometimes minute to minute. We had a roller-coaster ride trying to keep her alive," says Jeffers, who for two weeks thought his daughter might not pull through.

"She deteriorated quickly in front of us," says Dr. Deborah Franzon, the pediatrician who treated Malyia when she arrived at Stanford. "She needed life support and blood pressure medications to help her heart functioning."

While the doctors managed to save Malyia, not enough oxygen was getting to her limbs. Because of that, Franzon said, three weeks after she arrived at Stanford, surgeons had to amputate her left hand and some of the fingers on right hand. They also had to remove her legs below the knees.

Methodist Hospital said it could not legally comment on the Jeffers' case.

"At Methodist Hospital, patient care and safety is always our top priority" said communications manager Bryan Gardner. "Patient privacy laws do not allow us to discuss specifics of this case. We were sorry to hear about the eventual outcome for this little girl and our thoughts and prayers are with her and her family."

Emergency room wait times a national problem

According to a 2009 report from the Government Accountability Office, emergency department wait times continue to increase. The report says the average wait time to see a physician is more than double the recommended time in some cases.

Research from Press Ganey Associates, a group that works with health care organizations to improve clinical outcomes, finds that in 2009, patients admitted to hospitals waited on average six hours in emergency rooms. Nearly 400,000 patients waited 24 hours or more.

"It's not unheard of to wait that long in the best hospitals, and even in the best emergency departments," says Dr. Assaad Sayah, chief of emergency medicine for the Cambridge Health Alliance in Massachusetts. "Overcrowding is not just an emergency department problem, but a hospital inpatient problem."

Dr. Sandra Schneider, president of American College of Emergency Physicians, says the backups occur as emergency departments struggle to find beds for admitted patients.

"Think of the emergency room like a restaurant where people come in and go out," she says. "Now imagine a restaurant where the customers come in, but never leave. They come in for breakfast, they stay for lunch and they're there for dinner."

When a patient is admitted to the hospital and needs to remain for additional procedures, they take up available inpatient beds leading to a domino effect, Schneider says.

"I wish I could have kicked in the doors"

Her parents believe Malyia's condition was the result of a recent ear piercing that got infected.

"It makes me angry to think about it," says Jeffers. He says he made many attempts to get his daughter the care she needed, and regrets he could not do more.

"I wish I had kicked in the doors to the emergency room and made someone see her sooner," he says.

Emergency department physicians offer these tips to help you both before and after your arrival at the emergency room.

BEFORE YOU ARRIVE

Find out if your hospital posts emergency room wait times

Many hospitals have started posting up-to-date estimates to help patients be more informed of their potential wait.

Even before an emergency happens, it's a good idea to figure out which nearby hospitals post their emergency room wait times on the internet, Sayah recommends.

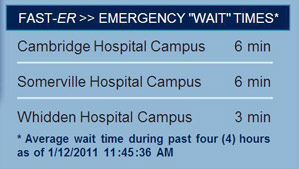

Many hospitals, including members of the Cambridge Health Alliance where Sayah works, have started posting up-to-date estimates on their homepages to help inform visitors of their potential wait.

Avoid high-traffic days if you can

Patients who have the option might want to consider when they choose to go to the ER.

"In most emergency rooms, the busiest day is Monday," says Sayah. "Patients who get sick on the weekend wait until Monday to go to the hospital because they don't want to spend their weekend in the ER," he explains. Studies have shown that patients who arrive in the ER on Monday rank lowest in terms of patient satisfaction.

Experts say parental instinct can tip off a parent to a developing problem, but say there are also some cut-and-dry situations when a parent really should take a child to the ER. [More tips on how to tell if it is an emergency in our column: When to take a child to the ER.]

Call your doctor on the way to the emergency room

"It's a good idea to let your doctor call ahead and tell the ER physicians what they may be thinking," said Schneider. Your physician may be able to explain your symptoms more clearly, and when ER doctors hear from a fellow physician, it might help put you on the radar.

AFTER YOU'VE ARRIVED

Don't leave once you're already waiting

"People often get angry or leave, but that's a bad idea," says Schneider. "If you were sick enough to be there in the first place, then you need to wait."

She says to note that triage nurses are sorting through dozens of patients and says don't be rude, but do be persistent.

Tell someone if you notice changes

"As you are waiting, if you notice changes in the patient, let the nurses know there is a new symptom as soon as possible," says Schneider. According to the Emergency Severity Index, triage physicians have specific requirements for assessing pediatric patients.

There are protocols in place to reassess patients in the waiting room and alerting the staff to changes in symptoms, especially to changes in temperature and fever, can help your child avoid an excessively long wait in the emergency room.

Ask for the charge nurse

If you have been waiting for a while, and feel like the situation is getting worse, ask for the charge nurse or shift supervisor. Experts in emergency medicine often define urgency using certain terms. They say to advise the person in charge that you think the patient has an "emergency medical condition that should be evaluated right away."

CNN's Elizabeth Cohen contributed to this report.